Critical Making

I'm engaged in a specific ideological exploration that is rooted in the intersection of community and identity. While I see connections and synergy, other see "projects." This gap represents a particular challenge for me. The core of the challenge is the confusion created by interdisciplinary work. There are countless examples of the trouble faced by interdisciplinary scholars, but the nature of success is equally harder to define. As an academic at a "teaching" school expectations are high that my classroom work will be exceptional. This does not mean I do not need to have a scholar agenda. Both of these goals require time and effort. There are numerous spaces on the web where those questions are explored in depth. My goal in this space to frame my activities.

Perhaps one of the most important things I reflect on is that one of the natural consequences of teaching is the drive to create clarity for the audience. This affects how you approach the classroom. For me, working in a luminal space between perception and reality around U.S. culture is a defining framework. I study the real and imagined city. These two states, the world we live in every day and the world we aspire or desire are always in dialogue. What you imagine does matter.

This year you can see how I've explored the effort to shape and re-shape the urban environment from multiple perspectives. My efforts have taken into account the transformation of the historic African American district in Winter Park called Hannibal Square and explored the broader African American experience in Central Florida. In the case of Hannibal Square, questions of African-American, city planning, and New South historiography come into play. Hannibal Square was part of the original design for Winter Park. As a result, Hannibal Square has been the home for property owning African Americans since the early 1880s. Today, it faces gentrification as development pressure transform Winter Park. In the Fall my critical making digital project for my United States Since 1945 course was to create an ibook examining the question of sustainability in Hannibal Square.

I talked about the "Blue Sky" elements of this project before. By examining Hannibal Square's story through the lens of U.S. experience around urban sustainability I'm able to challenge some common assumptions around gentrification. In this way, the critical making project intersects with larger discussions about the impact of gentrification on communities around the world.

In the spring semester I continued by engagement with African American experience with a project in my African American History Since 1877 that explored African American aspiration around education and work. Long cited by critics as failures within the black community, tracing the historical legacy linked to these issues can inform contemporary debates by making clear the racist barriers facing black efforts to learn. The obstacles placed in the way of African Americans pursuit of education and work are an important goal. Moreover, African-American History Since 1877 is a community engagement course, so I can incorporate assignments with more time and engagement. With this mind, my course design attempted a scaled cognitive structure that asked students to examine education and work through archival research and critical making. The first stage was an examination of the Rosenwald Schools in Florida. The story of Julius Rosenwald's support of black education in the rural south is known. However, the specifics can be hazy. We know that Rosenwald supported the construction of some 5000 schools working with Booker T. Washington. The database of the Rosenwald Foundation available through the Fisk University Library makes this much clear. We read chapters from Mary S. Hoffschwelle's Rosenwald Schools of the American South and essays on Booker T. Washington's Florida Tour and African American education institutions from Go Sound the Trumpet, an excellent collection of essay on African American History in Florida.

The course project asked students to examine the database to uncover more information about the Rosenwald Schools in Florida. Each student worked to create a short narrative for about 10 to 15 schools. In pursuing this goal students were able to learn more about obstacles facing African Americans around education, how Florida's experience could be contextualized in the post-Reconstruction South and some effects of the Rosenwald schools on the black communities across the South. Of course, the end result is always a mixed bag. Each student completed an annotated bibliography and a short essay based on the archival information they collected, but not every site got a full accounting.

The learning benefit in this process was that the entire class gained a clear understanding of the contours of the challenge facing African Americans, but some students examining individual sites do not gather deep information (in their defense, the information might not exist). Nonetheless, the combined efforts represented a significant investigation of the black experience. The class as knowledge collective is a particular kind of idea. I've attempted it in the past and I will do it again, but you never know what you will get o_O.

At the end of the process the final submission included uploading the information to a google spreadsheet. With the collected information, I was able to create an interactive map of the Rosenwald schools in Florida we explored.

The National Park Service took note of our efforts gave us a shout out on Twitter.

As is the way with digital projects, the process is not done. As I assess the project now, I see several paths it could follow. I will need take stock of the archival sources available and the ways a new iteration of the project may align with student learning in a different course.

While this mapping project in African-American History Since 1877 shaped the first part of the semester, we quickly turned toward an exploration of work in the second part of the semester. My design for the "WORK" project always intended the critical making project would have an public exhibition. The creation of a public installation allows information to reach a different segment of the public. While I embrace public humanities as a viable tool for teaching and scholarship, I've always understood that communities of color do not have the same access to digital space. To address this gap, I've turned to exploring the creation of visualizations that can be online or printed as posters.

For students working in this mode presents a particular set of challenges. We relied on the directory of the Orlando Negro Chamber of Commerce in the Olin Archive as our archival source for this project. Each student used information from its pages as starting point. As in the first part of the semester, our background readings included work exploring African American business history and economic impact of segregation. Each student completed an annotated bibliography and short essay based on their chosen subject. While these essays were informative for the students, the real challenge was bridging the gap between the general information and the specific circumstances in Orlando. We started the semester with knowledge that the Orlando African American Chamber of Commerce would serve as a partner for the project. I met with officers in the organization early in the semester, but scheduling conflicts made direct participation difficult. Nonetheless, the feedback garnered from early in the semester made certain themes around entrepreneurship, community, and agency in African-American economic experience as guideposts for the story we wanted to tell.

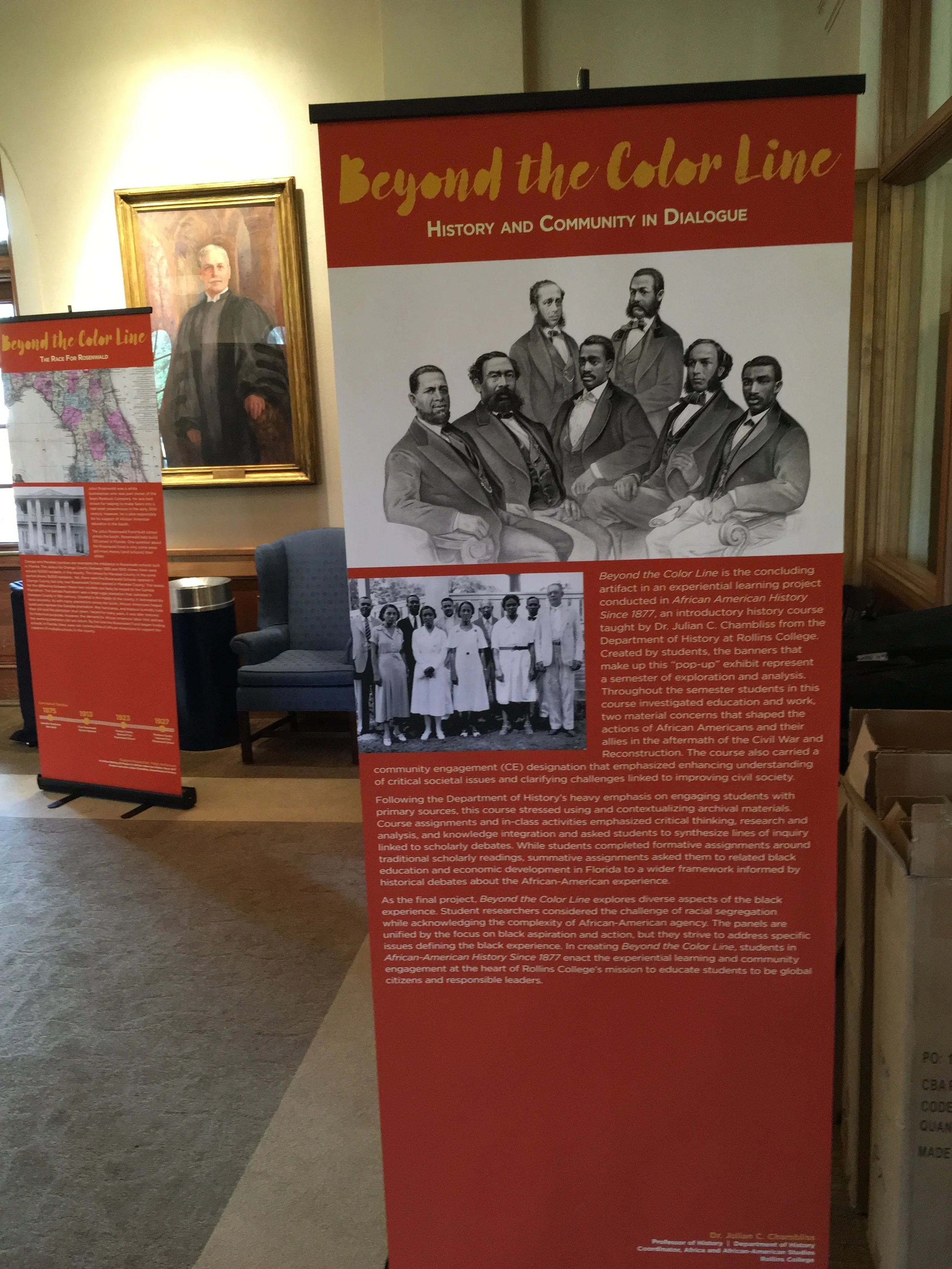

The final project was the designing and writing the panels that would create a "pop-up" exhibit that captured an idea linked to education and work for African Americans. Each student was responsible for two panels. However, they were required to synthesize information from the entire semester to create the panels. Research on education early in the semester needed to be re-engaged while they processed information from later in the semester about African-American business history. The unstructured nature of the assignment was a real challenge for some students. There decisions shaped what they did and many wanted to be told what to do or fall back on material they had been exposed to other classes. I explained that inquiry driven assignment like this can be uncomfortable, but the result are always unique. The process forced them to think critically about primary sources and analyze information using theory and examples found in secondary literature. We often talk about the benefits of the study of history is that students can apply this methodology to any problem later in life, but the reality is that our classes can create anxiety for students in the moment. I have said, "Don't worry about your grade, worry about making something cool." The look on students faces is always priceless.

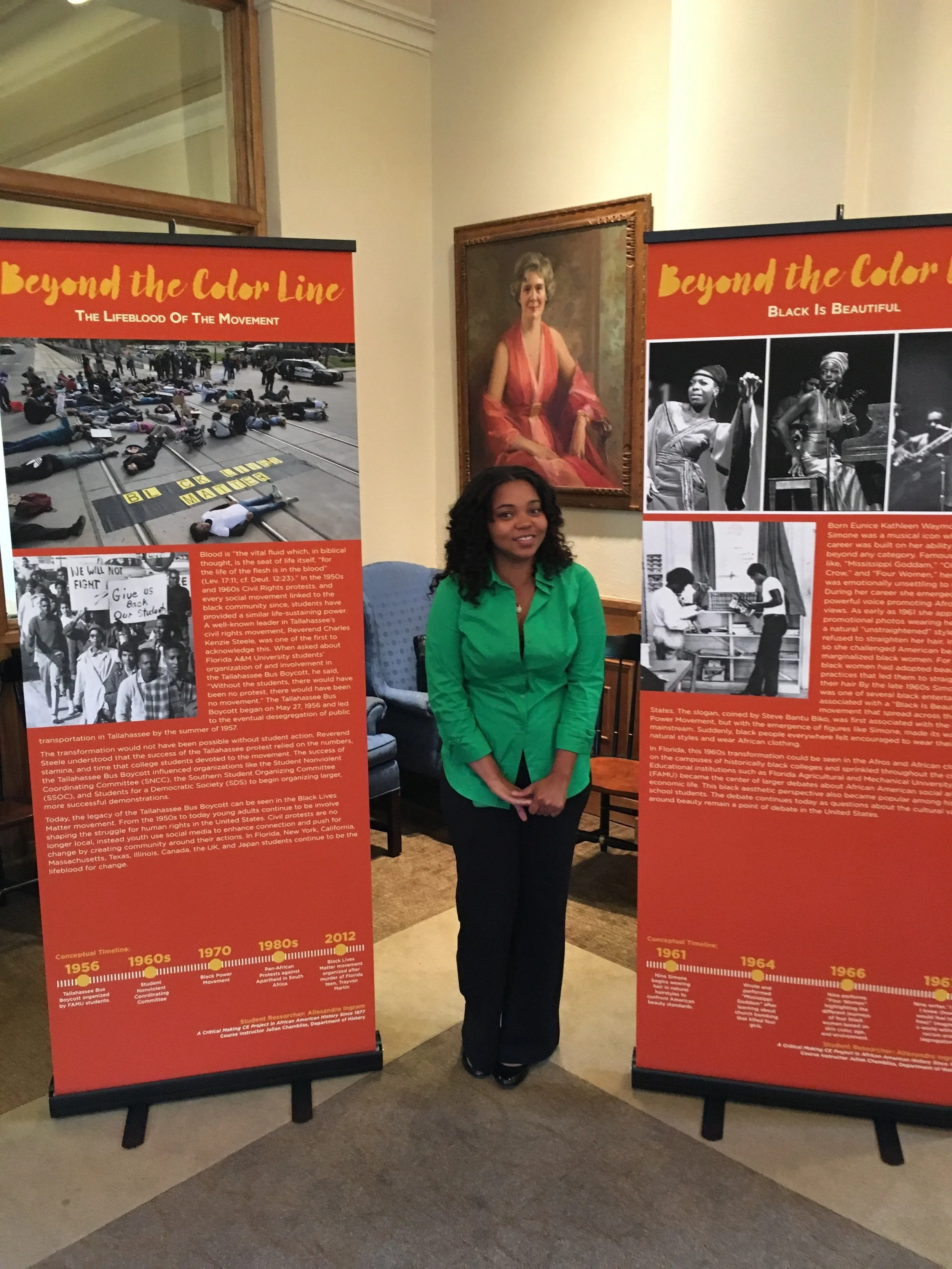

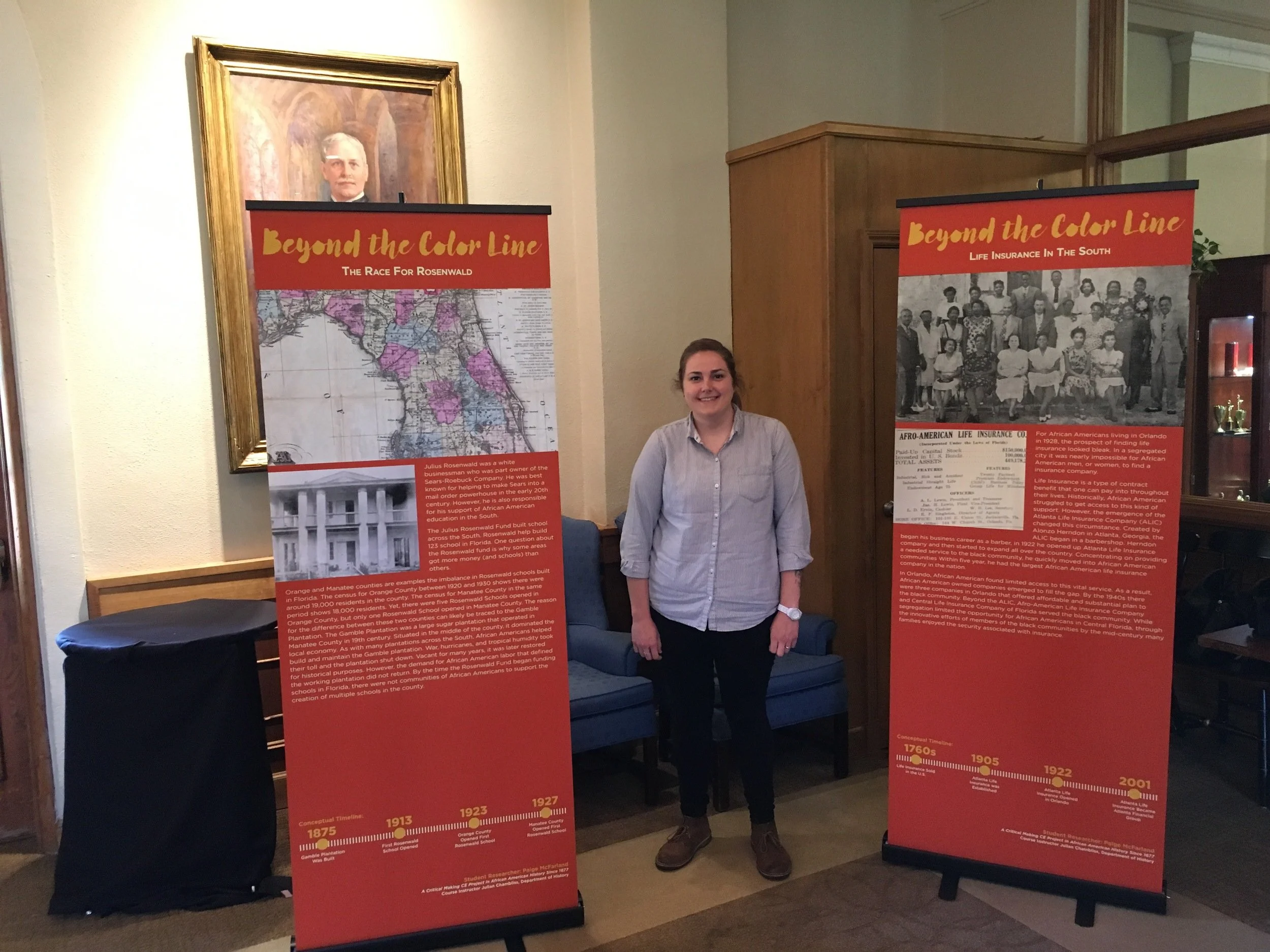

As we moved through the final part of the semester the student concentrated on writing their panels. We had support Jen Atwell, the graphic designer at our college print shop, to help us design everything. She was able to create a template using In-Design and we picked the color scheme and fonts during in-class design sessions. Outside of class each student worked to hone the text of their individual panels. My instruction for the panel emphasize using a clear thesis to drive the information on the panel. We talked about different techniques employed in museum panel texts including the use of imperative verbs, lists, and chronological structure. The end result is a portable exhibit called "Beyond the Color Line." BTCL is a series of individual panels that can be put on display as big group. As an exhibit the theme of the pop-up exhibit is focus on Florida's history around education and black business development in Orlando.

The pop-up provides the viewer with a framework to contextualize the work on display. I cannot say it is a perfect project. As is always the case with this kind of experiential teaching, I've learned a lot about the process by doing and that will help me create better outcomes the next time I do it. I believe I will revisit the BTCL project next time I teach African-American History Since 1877. By refining the process and shifting the content focus (politics seems the obvious choice), I can explore the African American experience while providing students with an important opportunity to dialogue with the community.

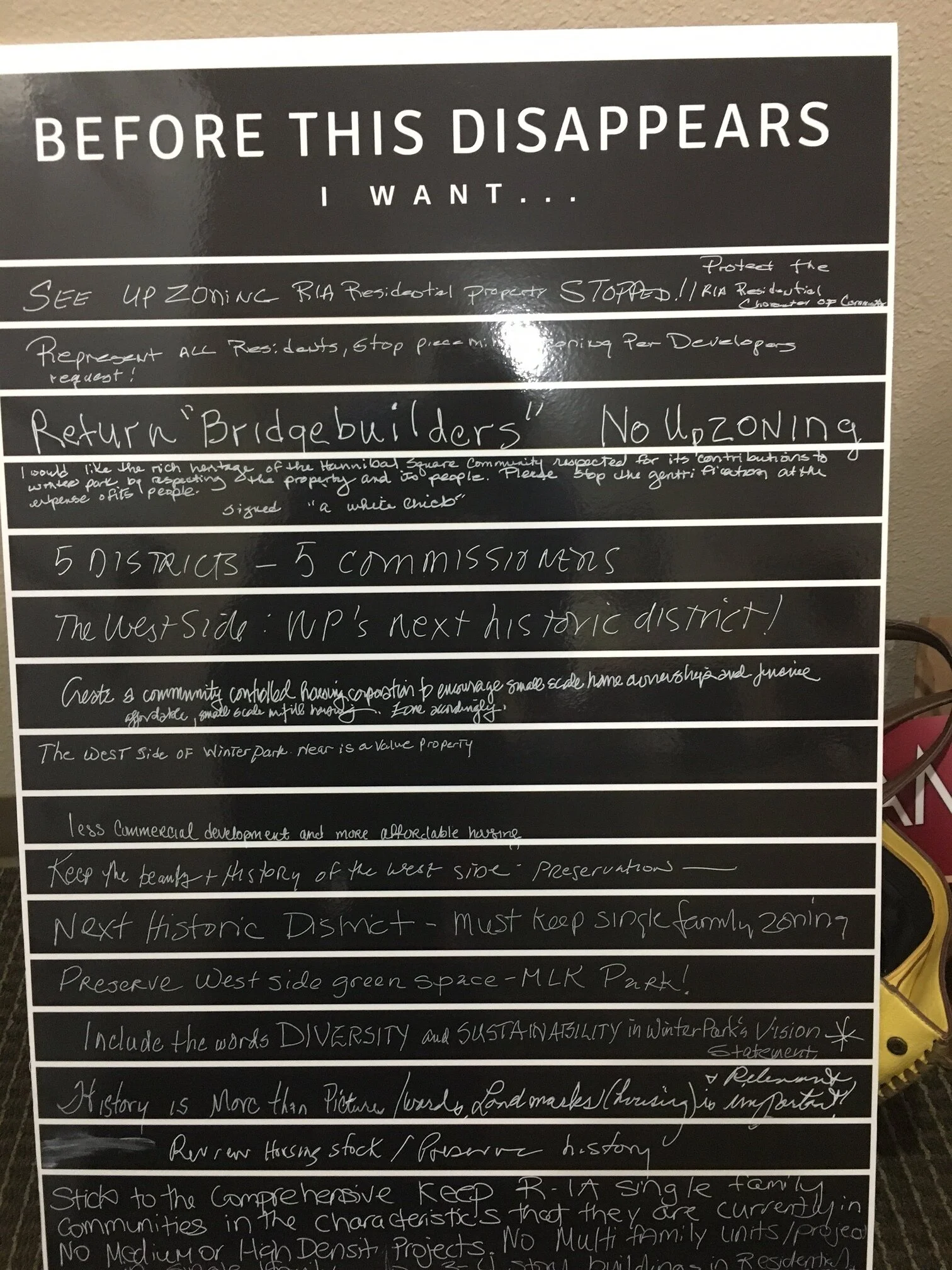

This point was made clear by the fact I gave a presentation at the Winter Park Community Center called, "Hannibal Square: The Evolution of a Dream" for local residents. Sponsored by the Winter Park Historical Association, the Hannibal Square Heritage Center and the Friends of Casa Feliz Historic Preservation group, this talk gave me an opportunity to linked the historic legacy of Hannibal Square with question of contemporary re-development. I pointed out that a legacy of under investment by the white community after the 1890s meant that the black spaces and property could not gain the value seen on "the other side of the tracks." The result is that Hannibal Square and the surrounding black community were easily seen as blighted once segregation came to an end. The effort to "improve" the community opened black property to market forces that have steady changed the community with little regard to the reality of past racism that prevented African Americans from improving their economic standing. While the literature on these issues is clear, I took the opportunity to engage with audience in public art intervention called Before This Disappears (BTD).

BTD bridged public history and art practice by asking audience member at my talk to articulate their desire about development in Hannibal Square. While this may seem a strange choice, I believe clarifying the historical narrative and then capturing public sentiments about development allowed for interesting community thoughts to emerge. The comments capture an awareness community history and complex politics that a Q & A might have missed. This process is not done. I have agreed to give the talk again and as I do so I will continue to capture these comments from the audience.

These efforts coincide with digital projects in my HIS 265L Digital History course that have explored Hannibal Square. HIS 265 was an experimental course that focus exclusively on learning about and implementing digital pedagogical projects. This class was oriented around the Advocated Recovered, a transcription project that is recovering the content of a black owned newspaper published in Winter Park in the 1890s, digital mapping techniques, and using the Mobile Academic Research Application (MARA). I discussed by efforts with Advocated Recovered at Matt Delmont's Black Quotidian project. In that post, I highlighted the importance of recovering the content of African-American newspaper from the late 19th century. Other projects in the course had merit as well. My effort to introduce the importance of mapping to students allowed them to understand how spatial awareness can shape understanding. Finally, our efforts to use the app I've developed in conjunction with our Instructional Technology department made clear its functionality to excite students and allowed me to develop lesson plan designed to explore the community. As a "topics" course it was experimental, but much of critical making projects in the course serve to explore the community. I'm especially pleased that the Advocate Recovered stands as an accessible archival resources open to students and scholars interested in the black experience in the 1890s. It is not done, but as a generative pedagogical project, it can generate new learning even as I continue to build on its content.

What does it all mean?

Good question! I see Hannibal Square as part of a broader black social world in the New South. In my teaching and my research I'm working to understand the implication of that experience. Whether the article I'm working about Hannibal Square in the 1890s or the open electronic resource I'm creating in the Advocate Recovered, the black experience after in the New South becomes clearer through the lens of local history. The period that covers the post-Reconstruction period to the Great Depression is a crucial one for understanding how antebellum ideology around race and racism were re-produced and infused into the postbellum reality facing African Americans. The rise of segregation and the creation of the Jim Crow South were willful acts of white supremacy and understanding the legacy of those actions animate my hybrid approach to teaching, scholarship, and community engagement.